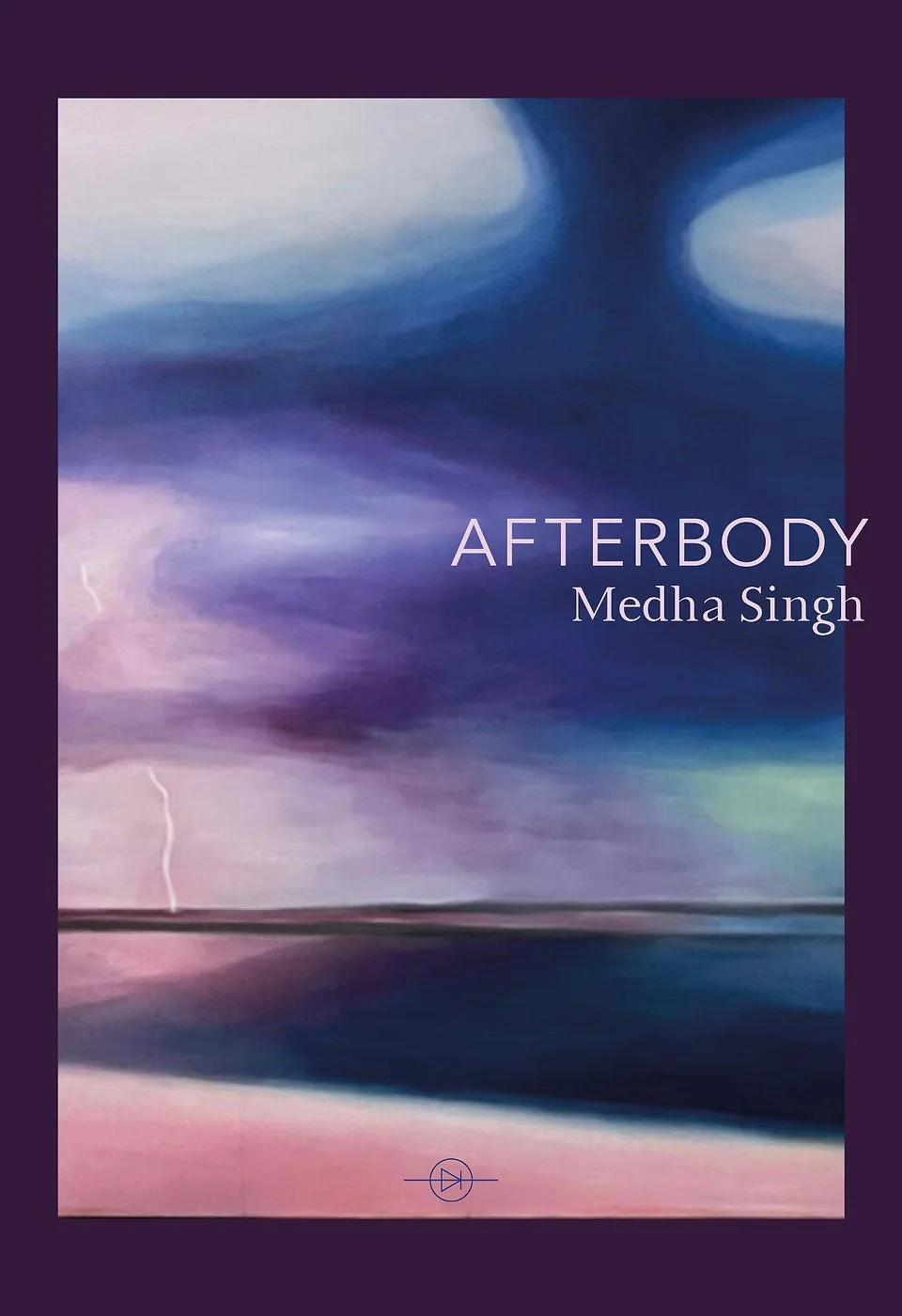

Afterbody

Medha Singh

Reviewed by Chinmaya Lal Thakur

After reading Medha Singh’s debut poetry collection Afterbody, I was reminded of the phrase ‘violent yoking together of opposites’, originally used by Samuel Johnson to criticise the poetry of John Donne and Abraham Cowley. Johnson felt that Donne and Cowley forcibly juxtaposed heterogeneous ideas, images, and conceits in their writing. However, soon after the end of the First World War, T. S. Eliot revisited Johnson’s negative characterisation of those Metaphysical Poets. He argued that Donne and Cowley in fact did well to undertake such collocation because their writings brought about new possibilities in aesthetics and ethics.

Similarly to Eliot’s reinterpretation of Donne and Cowley, I feel the poems in Afterbody bring together different subjects, images, and ideas in order to generate fresh potentialities in politics, aesthetics, and ethics. These potentialities not only reflect Singh’s nuanced and assured inheritance of modernist techniques but also her awareness that sometimes things only appear completely opposed to each other. Apparently discrete and disparate concerns, in other words, are actually connected to each other in Afterbody, because the poet establishes a meaningful resonance and conversation among them. In ‘Edinburgh, Spring’, an early poem in the collection, for example, light begins to purple ‘as a clot’ on the speaker’s thigh and men who are ‘heavy/with septum piercings’ enter the space ‘to teach the unloved / how to dance with fire’. The speaker is yet to recover from the impact of the ‘light’ and is thus ‘slightly euphoric’ when she ‘sees’ the following calm sight to the left:

…a child

sleeping on his father’s stomach

who sleeps inside the stomach

of a hammock, lulled

by the warmth of body and day.

This scene clearly does not allow the speaker to rest in any kind of euphoria. As the poem concludes, the view of the father and his child lulled to sleep is, ironically, bound to bother and disrupt the poet's sense of self. This is just one of many such possibility-generating disturbances which are present throughout Afterbody.

The tension generated at the conclusion of ‘Edinburgh, Spring’ is mirrored in two parts of the longer poem ‘Painting Our Time’ which marks the end of the first of the four sections of the collection. These two segments, nos. 5 and 6, themselves represent the juxtaposition of the personal with the public. In segment 5, the eyes of the speaker’s mother well as ‘she casts [her] father’s bones/into the ceramic waters / of the Ganges’. At the very moment that her husband is ‘swimming away into the after’, there is an empty beehive that ‘still sways, hangs / on the porch of her home in the village’. Similarly, in segment 6, the speaker addresses farmer distress in India. In an angry and sarcastic tone, she claims that the farmer should be praised for unburdening ‘the land of his own weight’. His children, meanwhile, should be praised for wishing that he had not hung himself but ‘taken poison instead’. And then the village should be praised for knowing ‘poverty / as pestilence’. Then, lastly, the woman too should also be praised for forgiving him.

Much like the aforementioned reference to spring in Edinburgh, reality reconfigures again in the cityscape of New Delhi, especially in the second and third sections of the collection. At the conclusion of Movement 1 in ‘Aerie: Vignettes, Delhi’, for example, the poet presents the farmers’ protests against the three farm laws enacted by the government of India (2020-2021) vividly. In a short poem or vignette of two sentences and three lines that resembles a concise prose paragraph, she is able to bring out the immediacy of moments as well as take a retrospective glance at the protestors’ feelings and motivations. The characteristic disturbance at the end of the vignette takes the form of a heart that is ‘half-breathing’ and ‘half-beating’.

They stand, here they stand, unfit and a tad too sensitive to peachy sundowns:

dog and god, homeless together day after day, beneath starless, smoggy nights,

but for the subtle call of the great, white speckle: Venus masquerading as the

north star.

Here they are, asking, why are you here, half-breathing, half-beating heart?

Singh is adept at establishing resonant connections between past and present throughout Afterbody—between people in the now and those who have featured in classical literatures in both prominent and marginalised ways. These connections feel organic and unforced as Singh’s references to Atlas, Sisyphus, the Bible, Dante, Virgil, Donne, and Rabelais, among others, are worn lightly in the poems. A vignette towards the end of the third section of the book is a good example of this. Here, a woman who sweeps the streets of Delhi in the city’s sweltering heat between the months of April and July is to be identified. The speaker asks what her name and designation may be, suggests that she could be ‘Dante’s guide’, ‘Beatrice [?]’, and then appears to have doubts about her own suggestions. In the second verse, a young man, the lover, is similarly (un)identified as ‘…not Virgil’.

There he is, flowing between alleys—

London, or Delhi. His back is turned to me, he’s toying

with an old pocket watch. When I first looked at him, I saw

the nervous gaze you do on young men’s faces. Then

something else: my face, it reminds him of all

the women that make them run: Man’s soul, always

out of time.

Like the dissonance at the conclusion of ‘Edinburgh, Spring’ and ‘Painting Our Time’, the concluding line here disturbs the overall pattern established by the poem—the pattern of the speaker encountering people and situations that she can generally understand, control, and regulate. Who is to guarantee, in other words, that her soul too has never been, and will never be, ‘out of time’?

In summary, throughout the collection the speaker constantly struggles to make sense of what she sees, feels, and experiences. She compares these sensations with those from the past and tries to imagine what the future may look like for both herself and for the places in which she lives. This unceasing, restless struggle not only makes Singh’s poetry in Afterbody vital, alive, and resonant but also makes readers look forward to what she will do next.

First published in Issue #33

Chinmaya Lal Thakur teaches English at Shiv Nadar University, Delhi/NCR, India. He has recently completed his doctoral thesis on the writings of David Malouf from La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia. He has published several journal articles and critical reviews, and he also translates creative writing between English and Hindi.